Versioning is a tool which allows microservices to gain independence from each other while being able to grow and change. Its critical that when we make changes to a microservice we can do so in a way that we are confident will not break our consumers.

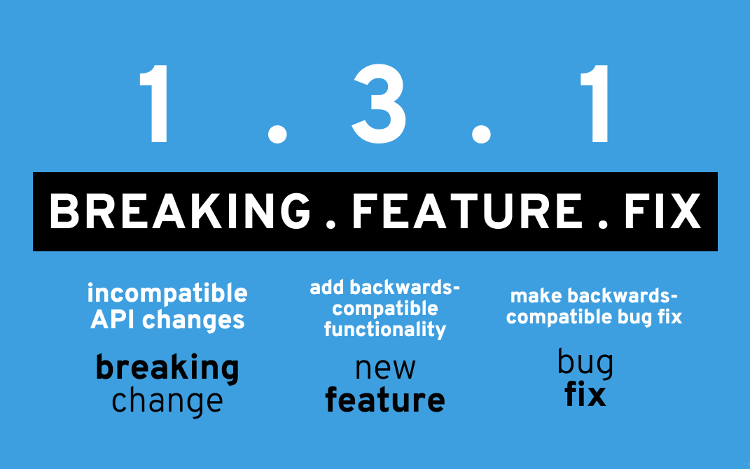

Semver is a great way to think about versioning, as a refresher semver uses the following versioning:

When we are thinking about microservices we need to be concerned about the versioning strategy from both the point of view of provider and consumer. However as we have a live system we actually only need to worry about making breaking changes to our services (ie the first semver number). If we make any non-breaking (feature/fix) change our consumers don’t need to take any action. If we want to be able to make a breaking change to a service we must provide a way of making that change while still supporting the old version of the contract.

Versioning therefore lets us make breaking changes without breaking things. And lets face it, you will want to make breaking changes at some point in the life of a microservice.

What is Breaking

Breaking changes are any change to the contract which is provided by the service which is not backward compatible. There are many different types of changes which could have the potential to be breaking.

Transfer schemas

The transfer schema is the structure of the data you will either receive or emit in response to an external request. In HTTP this includes any response payload and the structure of posted content. In a messaging environment this includes events which you emit and commands you receive.

A breaking change is anything which would cause an old version of one of these formats to be unacceptable. While this may depends on the serialisation you use examples may include:

- Deleting a response field

- Adding a required field to the posted content or a command

- Renaming a field anywhere

- Retyping a field anywhere

- Removing support for a format (eg moving from XML to JSON)

Generally the following are non-breaking:

- Adding a new response field

- Deleting a field from the posted content you expect or a command

- Adding support for a format (eg allowing a new datatype, or content type negotiation in HTTP)

Endpoints

Endpoints are the place another service would go to connect to your service. They are just as important when versioning as your transfer schemas. In http this is the URL, in messaging the source you are listening to commands on or publishing events to and your routing information.

Breaking changes may include:

- Changing the URL structure

- Adding required information to the query string

- Removing routing information from an event

- Changing the command source or event destination

Generally the following are non-breaking:

- Adding new query string parameters

- Changing a URL while redirecting the old one

- Adding new routing information to events

- Changing the command source while redirecting from the old one

- Changing the event destination while redirecting to the old one

NOTE: its a good idea to document that your HTTP services may return a redirect response to allow you to change URLs without introducing breaking changes.

Performance

If you have given any guarantees about the performance or uptime of your service these are part of your versioned contract. Loosening the SLA you have is a breaking change as other services may have made downstream promises relating to your SLA.

Data

In most cases the actual data (not the schema) does not need to be versioned, however its important to be careful of implicit schemas especially in text based data responses. Its good practice to assume that any text based content has no internal structure, if it does its better to use a defined, versionable type instead of free text based data.

Versioning Methods

There are many different ways of versioning, different communication types will also use different methods.

HTTP URL versioning

This is the most common way of versioning for HTTP based services. In URL versioning you would put a breaking change version number in the URL, for example https://api.staticvoid.co.nz/v1/do-stuff and then when you make a breaking change provide a second URL with the new change https://api.staticvoid.co.nz/v2/do-better-stuff. This means that if someone calls the v1 URL they will still have their request serviced but new consumers will be able to use the new API.

HTTP content type versioning

Content type versioning exploits the content negotiation feature of HTTP to implement versioning. In this type of versioning the caller will request the version(s) which they are prepared to accept (using the accept header). For example accept: application/json+staticvoid.blogpost.v1 this signals that the response content type must be a version 1 blog post typed object represented in JSON. This is an elegant solution as it enables versioning per transport model.

However content type versioning comes at the cost of code complexity on both consumer and receiver. It also only addresses transport model versioning which means that you either need another versioning scheme to deal with other types of breaking changes.

Message routing key versioning

When versioning messages each message can be independently versioned. One way of versioning messages is to put the version into the routing key. For example my-type.v1.otherstuff (rabbitMQ style). This means consumers can receive older versions by subscribing to older routing key versions.

In this method the event publisher is required to publish using all supported routing keys, so if there are two versions two messages would be sent, one v1 and one v2. When handling commands the roles are inverted so you would have two handlers one for v1 and one for v2.

Making a breaking change

The whole purpose of versioning is to be able to make breaking changes without breaking things. While versioning adds a lot of overhead it allows breaking changes to be made which will let you progress your service to new and better contracts.

When making a breaking change you will need to publish a new contract for your service as a new version and then implement the required code to fulfil that new contract alongside the existing supported contracts. In practice I have found its often useful to point the old implementation at the new one and then manipulate it to fulfil the older contract, this allows your code to be DRY and means that bugfixes will be published to both versions at once.

Contracts for deletion

Versioning will leave you supporting older versions for a period of time. If you have no contract around the lifetime of a service it is implicit that you will continue to support that service for the foreseeable future. This isn’t a bad strategy but it will increase the drag of development as you will have to support old versions for a long time. I find it is useful to be explicit about the expected lifetime of each version.

A good way to do this is to document an end date for the version in your service documentation. For example you might say that on all current leading versions they are supported for a minimum of the next 12 months, and for an old version you can then say its supported until 12 months after it was superseded. This means that you are upfront about the period of support. This period may vary between services.

At the end of the deletion period you are free to delete the old version or maybe if traffic is still going to the old version 301 to a newer version and expose the consumer to the breaking change (which in many cases may not actually cause an issue for the explicit use case of the consumer).

Summing up

Versioning is a powerful tool which enables you to iterate on the contracts you provide from your services in a way that gives a clear and consistent experience for consumers. It is critical for allowing microservices to grow and change over time without causing cascade failures to their consumers.