I love simple reusable code.

I have used the repository pattern extensively as a way to achieve reuse and cluster my query logic into a single place. This is great as it means my queries can be reused and I know where to go to fix a database problem. However over the years I have encountered a number of problems with repositories.

Five issues with traditional repositories

The super generic method

In order to gain reuse on a repository method it takes a whole heap of parameters so that it fits all the places and specific scenarios which might use this repository.

eg:

public IEnumerable<Person> FindPeople(

string name = null,

int? olderThan = null,

bool includeAddress = false,

int? page = null,

int? pageSize = null)

This kind of method is usable in a lot of places which is great, but it lends itself to increasingly complex implementations which are hard to test.

The illusion of reuse

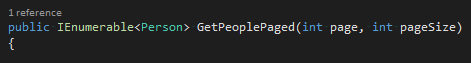

Visual studio 2015 has an awesome improvement, it lists out the number of places each method is used. But do all your repository methods look like this with only one consumer?

Sadly while we have built this method to be reusable in reality there is only one place in our application where we need a paged list of people. In fact almost all of our repository methods are specific enough that we only use them in one place.

The where do I put it problem

Say you want to find all of the people which live in a specific region. Where do you put this? Does it belong in a repository that deals with people? Or one that deals with addresses? Do we need a new repository entirely to deal with this new region based concern? Is it OK to return a list of people from a region repository?

Ever struggled with this kind of thing? Naming is a hard programming art form.

The close enough overfetch

Say you have a repository which will give you a list of people. People have addresses and when you list out all of the people in your neighborhood you want to see all of the addresses of the people. So you join onto the address table and populate an address property on each of your people. But sadly you have also performed this unused join for every other consumer of the method. This causes an overfetch problem where you are returning more data than you need and wasting resources. Most of the time this problem doesn’t amount to enough extra load to bother solving but its still there.

The reuse by underfetch

We have two repository methods, one which gets a list of people and another which gets an address for a person. To get reuse in our code we call two repository methods

eg:

foreach(var person in personRepository.GetPeoplePaged(1, 100))

{

var address = addressRepository.GetAddressForPerson(person.Id);

//other things...

}

As you can see this will create a performance issue (101 queries where one could have done), but sometimes its less visible than this.

Extension methods to the rescue

Most of us are using an ORM with a LINQ provider. What these do is to use an IQueryable to compile a deferred query and then execute that later (when we enumerate the set).

This provides an interesting avenue for writing repositories using smaller much more reusable chunks.

Consider the following repository call to generate an MVC view:

var people = personRepository.FindPeople(includeAddress: true, inRegion: "The Shire", page:10, pageSize: 20);

return View(people.Select(p => new PersonViewModel {

Name = p.Name,

Address = p.Address?.PostalAddress

});

As you can see we are calling our Super generic method and then converting this to a view model. However there’s a couple of issues with this.

- Its readable but its hard to follow the intent

- We are using our Super generic method which is a bit hard to test, and people are constantly editing it to do specific things they need.

- There’s a subtle overfetch going on here, we are querying for all columns of person and address but only using two.

What if we could write it like this:

return View(

Context.People

.InRegion("Shire")

.OrderByName()

.Page(1)

.ToViewModels()

.ToArray());

Looks much simpler right? Its less code and the intent is clearer. What if I told you the generated SQL for this also only selects Person.Id, Person.Name and Address.PostalAddress?

So how do we make this kind of code a reality? How does it work?

To do this we have 4 extension methods. Each performs one simple manipulation and supports chaining.

public static IQueryable<Person> InRegion(this IQueryable<Person> people, string region)

{

return people.Where(p => p.Addresses.Any(a => a.Region == region));

}

public static IOrderedQueryable<Person> OrderByName(this IQueryable<Person> people)

{

return people.OrderBy(x=>x.Name);

}

public static IQueryable<T> Page<T>(this IOrderedQueryable<T> entities, int page, int pageSize = 3)

{

int skip = Math.Max(0, page - 1) * pageSize;

return entities.Skip(skip).Take(pageSize);

}

public static IQueryable<PersonModel> ToViewModels(this IQueryable<Person> people)

{

return people.Select(person => new PersonModel

{

Name = person.Name,

Addresses = person.Addresses.Select(a => a.PostalAddress)

});

}

So that’s nice but what about our reuse?

Say we want to use the same view model but only find a single entity.

return View(

Context.People

.InRegion(region)

.WithName(name)

.ToViewModels()

.FirstOrDefault());

As you can see we still get to reuse the bits we already coded.

Noteworthy

- As with all ORM based code, be sure to check your generated SQL is sensible.

- Stick to collection based operations as the provide better reuse and SQL is a collection based language.

- You don’t need to project directly into your view models. You can just as easily project into your data models and use

.Includewrapped in an extension method to do your projections. This is simply an optimisation for simple queries. - You need to follow the rules within the extension methods, when you are acting on the collection you can only use methods which can be translated to SQL.

- In the examples and sample project I have used EF. However this technique should work with most LINQ providing ORMs, the bits that will differ will most likely be around how projection works.

Summing up

What this pattern gives you is what I would term a composable repository. Its a looser construct than traditional repositories, but very expressive and powerful.

I have put an example application on GitHub that you can check out. The two example methods mentioned in this post can be called with: